By Maya Hey

Tucked away in a municipal park sits a medical library, the Hagerströmer, which is a part of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm’s northwest. The building is regal in content, but plain and unassuming by its exterior. Without the flashy pizzazz of modern museum advertising, I could’ve easily missed the entryway. But I soon notice the bright green signage of the art exhibit I’m after, a characteristically noxious and alarming hue, which is true to the exhibit’s theme.

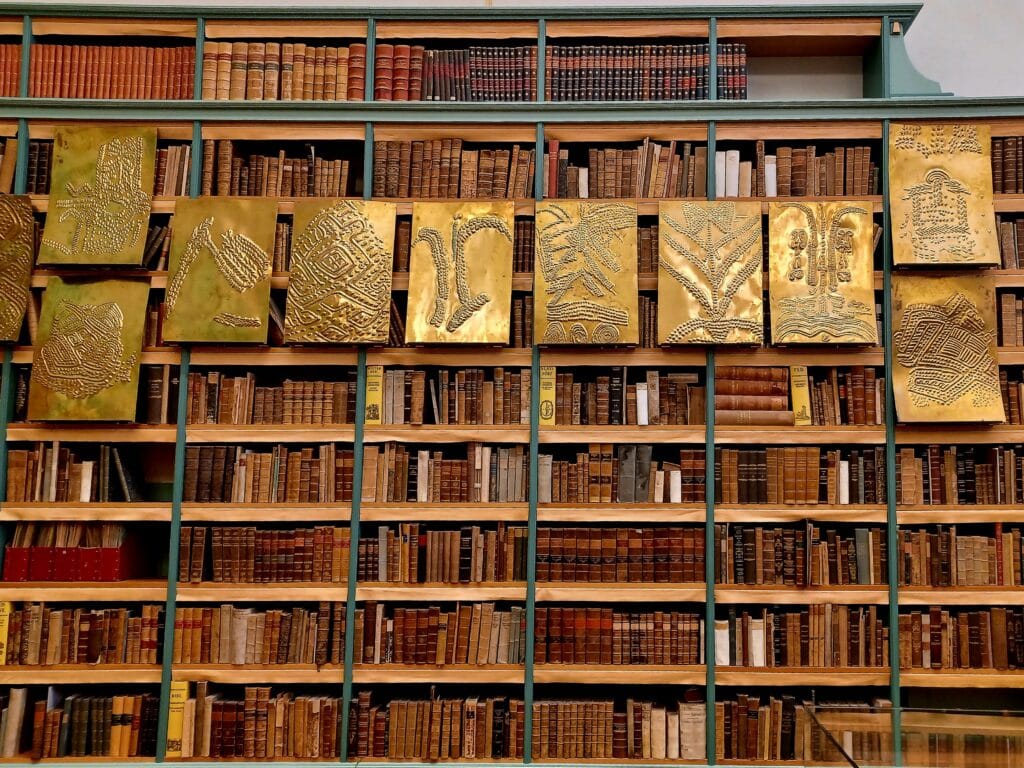

I sign up for a guided tour of the exhibit “Toxic Transits,” co-curated by Nicholas Cheng and Beatrice Brovia. Two other docents escort me up some stairs to the wing with the installation. Along the way, I pass life-size plastic models of anatomical figures and glass cases of metal instruments. As I enter the exhibition space, I take notice of the high ceilings and a glass chandelier that hovers above a central walkway where eight artists’ work are displayed. Their pieces are flanked on either side with rows and rows of medical texts, bound and aged in various shades of leather. “Toxic Transits” seems to be an overlay on the medical library; or, rather, the medical library is as much a part of the conversation in this exhibit, by reminding us constantly that toxicants are medico-material matters that affect us all–and differentially.

“Toxic Transits” asks: what is toxicity as a concept and agent, how does it shape human and more-than-human temporalities, and how does toxicity range across bodies and environments? With displays ranging from ferrous waste in Spain to algal blooms near Brittany, the entire tour lasted approximately 75-90 minutes. Three displays grabbed me in particular.

Immediately noticeable are the brass ‘portraits’ of Sammy Baloji, whose work I’d seen at the Tate Modern last summer. The pieces hang amongst the book shelves with intricate cultural markings, dotted and patterned to mimic the Congolese practice of scarring. By synecdotal association, the mined copper (in the brass) shows how Congolese bodies are made vulnerable and hidden when mining precious metals to fuel the appetite for electronics sold in the Global North. Jennie Leino, a Swedish artist, makes explicit the materiality of everyday toxicants by showing mundane objects–like fertilizers, dyes, cosmetics, building insulation, and food additives–in the form of (re)mineralised rock. With rock pieces in brilliant blues and opaque smoothness, the artwork seems to have melted, remineralized, and fused the banal objects of everyday life, using their newly transformed states to blur the line between synthetic/natural substances we encounter–and take for granted.

Our Centre’s artist-in-residence, Alma Heikkilä, exhibited some pieces that examine the relation between gut bacteria and environmental pollutants. On one side, a large canvas sits along the display cases, painted to a flesh color, as if it is a magnified image of flattened intestinal lining. Small gel-like blobs dot the canvas in a range of sizes, shapes, and colors, representing what I imagine to be a mix of microbes and toxicants. Because it is left ambiguous which is which, the viewer is asked to think through the ubiquity of pollutants, the ubiquity of microbes, and also, the role of microbes and their wellbeing in relation to ours. To the left of the canvas is what looks like a cross-section of intestinal villi, with stubby projections to emphasize the maximized surface area from which our gut derives life-affirming nutrients and, by the same logic, from which our gut stands all the more exposed to pollutants in the environment. (With Leino’s re-mineralised rocks directly adjacent, one wonders about pesticides in the gut.) Combined, Heikkilä’s work reminds us that we are walking tubes, perpetually exposed to foreign substances that may or may not be metabolisable by the microbes who make our living possible. Her message isn’t normative or prescriptive but rather invitational; the viewer is guided to reflect on the realities of perpetual exposure when both microbes and pollutants are invisible (or invisibilised).

Throughout the exhibit, I think about Mel Chen‘s concept of animacies and their example of the agency in lead. I think about the porosity of bodies as theorised by feminist new materialists. I think about how the exhibition space used to be a courtroom before it was a library, and how all of these works point to present and latent legal battles of accountability when toxicants cause irreparable harm. I think about Simone Müller’s theorising of the toxic commons and how differential exposures recreate inequalities in the world. I think about Alexis Shotwell and the reality that we are always living in compromised times, but that this reality ought to galvanize us to pay attention, organize, and critically mobilise. I think about the temporal justifications in most of these toxicants and how our human penchant for short-term capital-gain should have us be called Homo myopiens.

This exhibit asks us to reconsider what it means to take seriously the long durée and global sprawl of toxicants, when most remain obscured and difficult to detect. “Toxic Transits” runs until May 2, with limited viewings. Details are listed below.

Exhibit Location

Hagströmerbiblioteket

Haga Tingshus

Annerovägen 12, Solna

Viewing Details

By appointment only

Contact Anna Lantz, hagstromerlibrary@ki.se

Guided tours are available at the following times:

17th April 2024, 11:00-12:00

17th April 2024, 17:00-19:00

24th April 2024, 11:00-12:00